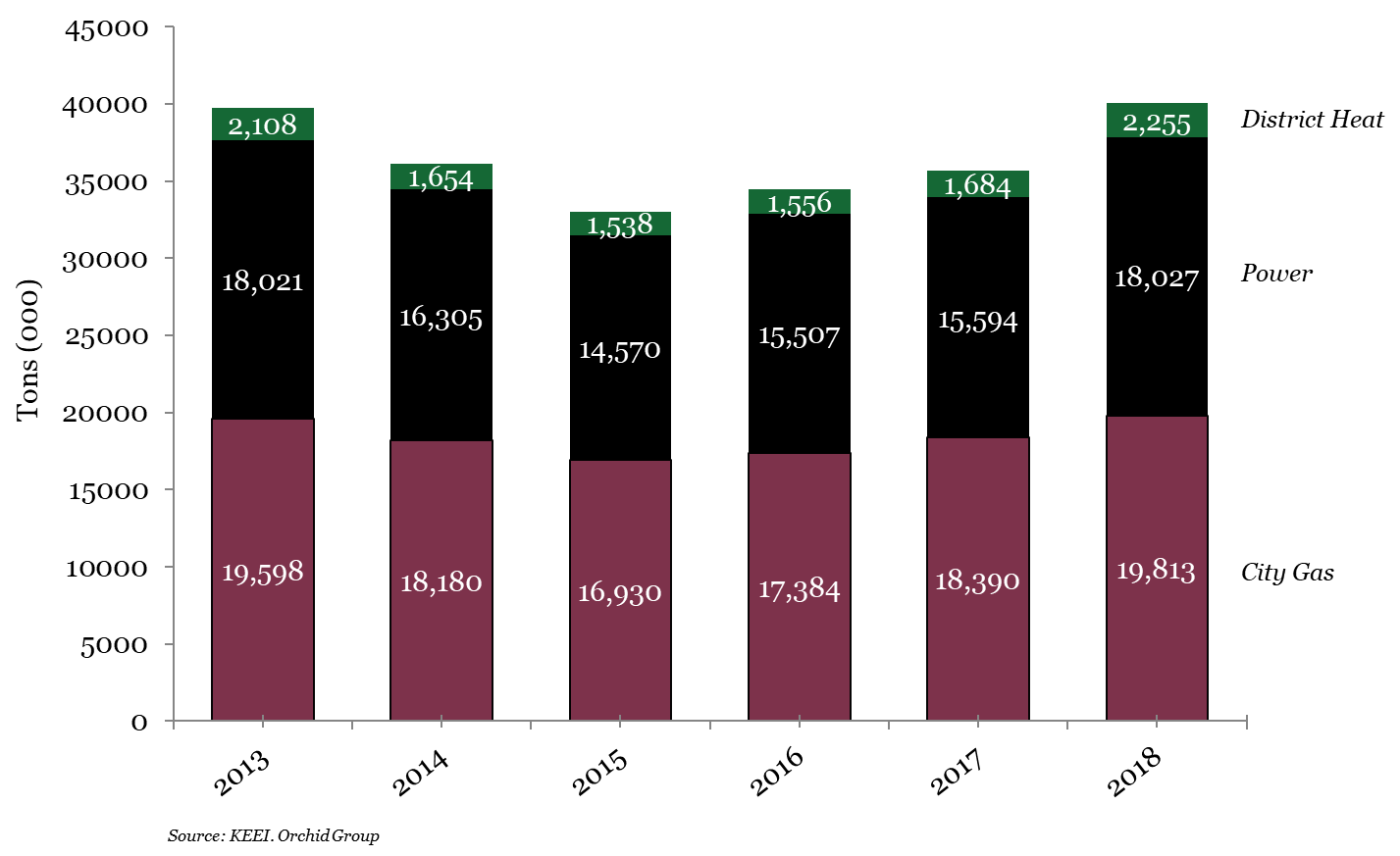

South Korea imported a record 44 million tons of LNG in 2018; a surprising 17.3% increase over 2017 imports. LNG consumption, not surprisingly, was also a record reaching 40.9 million tons, a 12.4% increase over 2017 demand and approximately 650 thousand tons higher than the previous high of 40.3 million tons in 2013.

This surge in demand occurred despite Korea nearing the end of a large buildout of coal and nuclear generation capacity that has put pressure on gas demand from the power sector since peak demand of 18 million tons in 2013. Coming as it did after four years of relatively stagnant demand, the key question for LNG suppliers and traders going forward is: was 2019 a one-off or a sign of things to come?

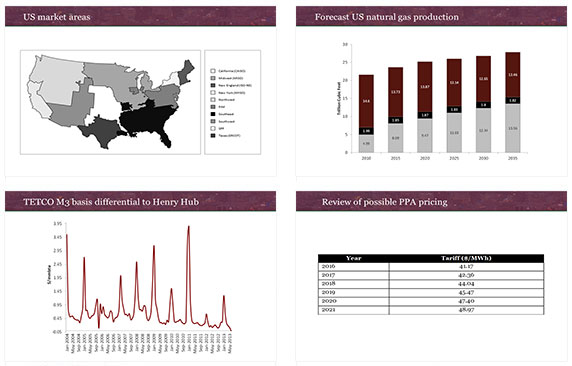

Breaking down demand

Gas demand in Korea was up in 2018 across all three key sectors: power generation, city gas and district heat. On top of demand, there was a build up of LNG in storage that accounts for the difference in the demand total (40.9 million tons) and the amount of LNG imported (44 million tons).

Korea gas demand by sector, 2013-2018

Winter 2017/18 was generally the coldest since 2012/13, pushing both city gas demand and gas consumption for district heat to new record highs. The average temperature in December 2017 was 3 degrees Celsius colder than in December 2016, leading to a year-on-year increase in demand from city gas and district heat of approximately 600 thousand tons.

December was followed by continued cold weather in January and February that resulted in a year-on-year increase in demand of 860,000 tons, putting pressure on gas in storage which stood at an unusually low 1 million tons by the end of February.

This triggered an initial wave of building up LNG supplies in storage in late winter. Record breaking summer temperatures, as well as other underlying issues in the power sector further discussed below, led LNG demand from May to August to outstrip demand over the same period in 2017 by nearly 1.6 million tons.

Fearing the same China driven high spot prices seen in winter 2017/18, over September to November, Korean LNG buyers – KOGAS in particular – loaded up on storage ahead of the winter. However, the combination of warmer than normal late autumn and early winter weather and continued stockpiling led to a record high amount of LNG in storage at the end of the year. The estimated 4.2 million tons of LNG in storage at year end was the highest amount of year end gas in storage in Korean history by nearly 900 thousand tons and higher than December 31, 2017 gas in storage by over 1.9 million tons.

The larger driver to demand growth, however, was the power sector. After four years of declining or stagnant demand from the power sector, 2018 saw a sudden jump of 2.5 million tons, narrowly beating out 2013 as the best year in Korea power sector gas demand history.

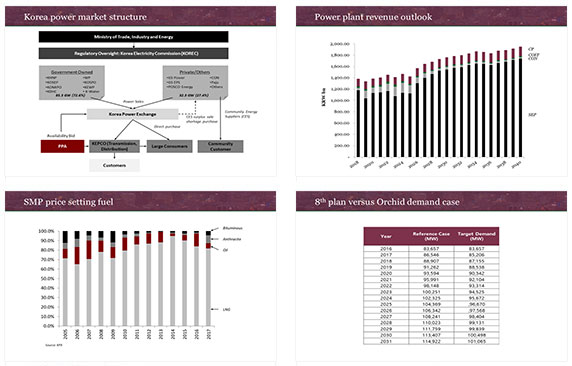

The decline in demand over previous years is anchored in the presidency of Lee Myung-bak. After taking office in 2008, Lee oversaw an energy plan that included growth in renewables, but also a new push into nuclear and coal-fired power. The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011 slowed the nuclear plan slightly, as did a nuclear scandal involving the use of counterfeit parts in 2012. However, throughout Lee’s term as well as that of his successor, who took office in early 2013, the baseload build out continued.

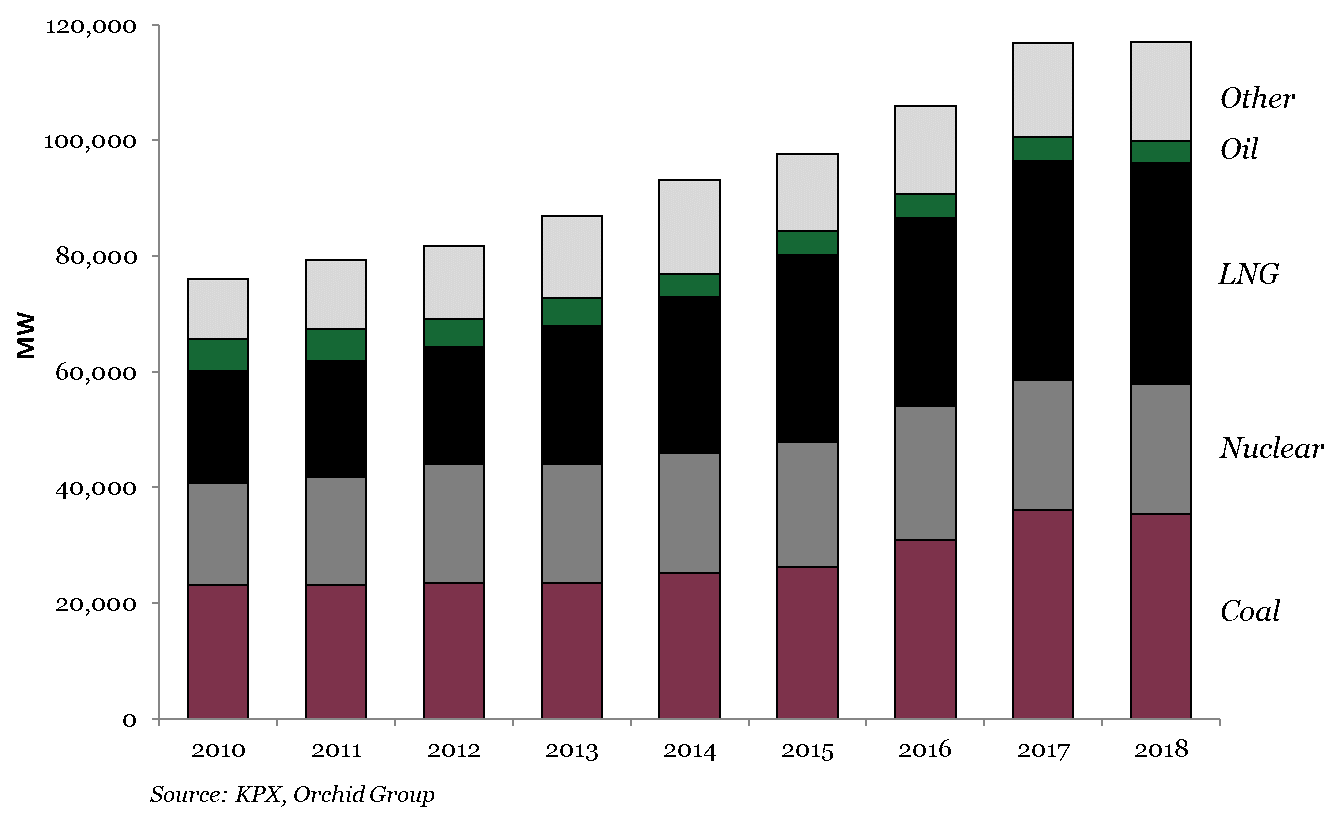

Installed power generation capacity, 2010-2018

By 2014, the impact of the new build program began to be felt. By 2016, gas-fired generators began to struggle significantly with plunging capacity factors and profit margins due to not only the growth in baseload power, but also an overbuild of gas-fired capacity that took place over the same period as Korean companies perceived a money making opportunity in the power market and poured into the space.

Between 2010 and 2017, coal capacity grew by 13 GW, nuclear by 5 GW and renewables by approximately 11 GW. In 2013, gas-fired generation was 119,875 GWh, 25% of electricity supplied to the market. By 2015, it had declined to 106,426 GWh or 21.5% of electricity supplied to the market.

In 2017, Moon Jae-in assumed office after the impeachment of Park Geun-hye. Moon arrived with a focus on improving air quality that focused heavily on transitioning from nuclear and coal to gas and renewables. One of his first acts as President was to decommission Kori-1, a 576 MW nuclear reactor commissioned in 1978 with a license to operate for thirty years that was extended in 2007 for a further ten years.

Separately, Korea Hydro and Nuclear Power Company (“KHNP”) took the 679 MW Wolseong-1 reactor offline in early 2018 and made the decision to decommission it effective June 2018, well ahead of its operating license which was extended in 2015 through November 2022.

In addition, Moon pledged to stop the extension of the life of nuclear reactors in the future, temporarily stopped construction of the Shin-Kori 5 and 6 reactors for review (construction was eventually allowed to continue), suspended the spring operation each year of the oldest coal-fired power plants in the country and pushed – unsuccessfully – to cancel nine new coal-fired power plants.

While the impact of most of these moves is longer-term in nature, nuclear power generation plunged in 2018 to 127,078 GWh from 141,278 GWh in 2017 and a peak of 157,167 GWh in 2015. Meanwhile, gas-fired generation surged in 2018 to 144,067 GWh, up from 117,637 GWh in 2017.

Will gas-fired growth continue?

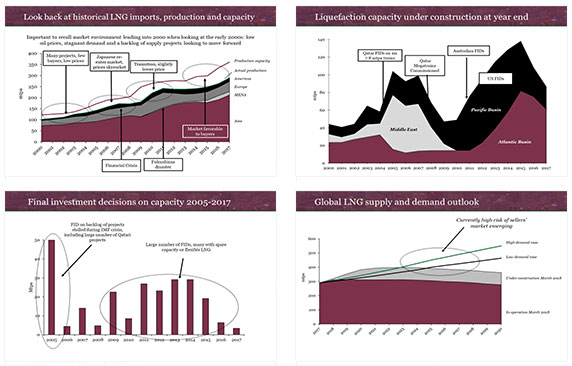

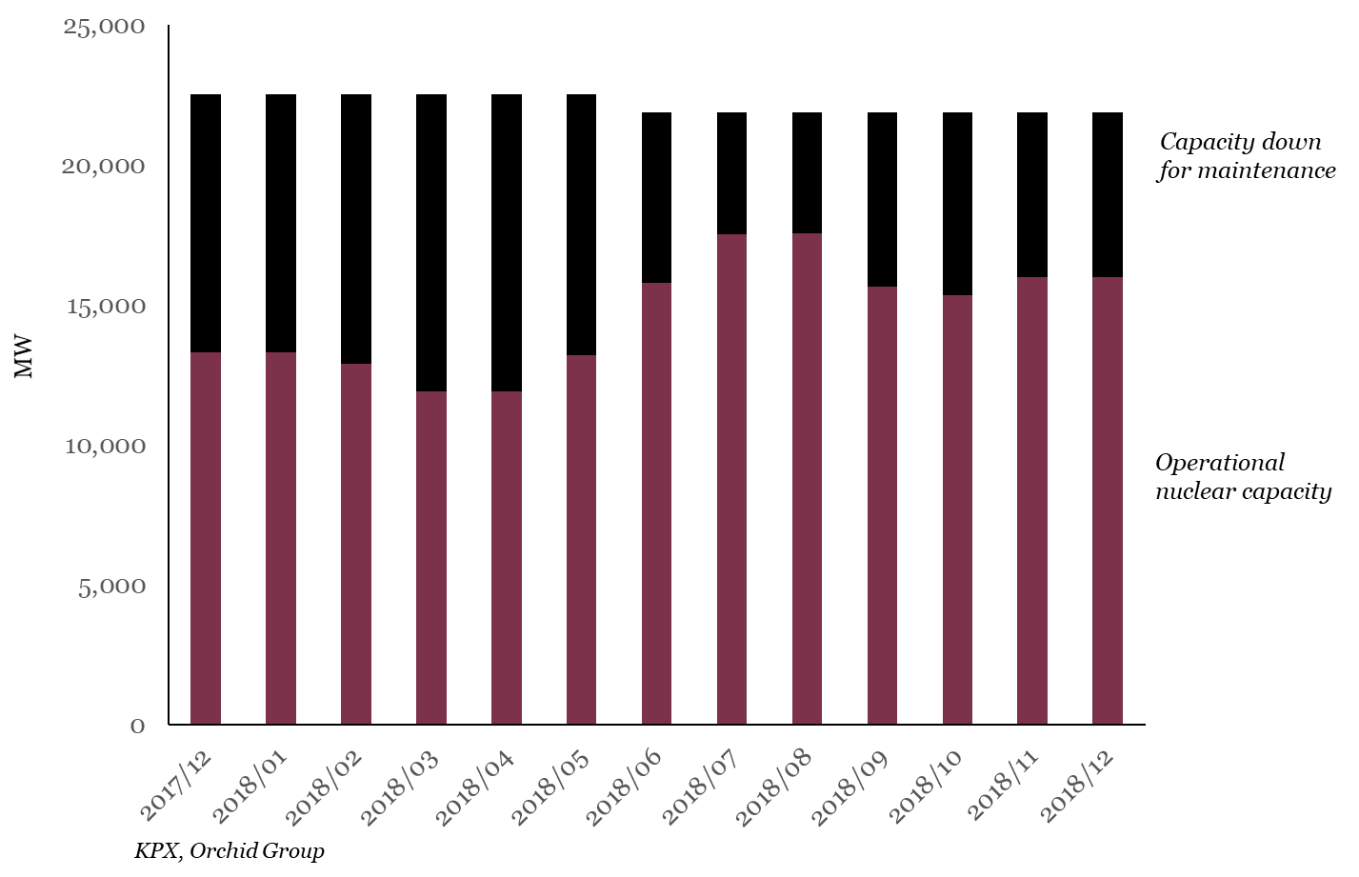

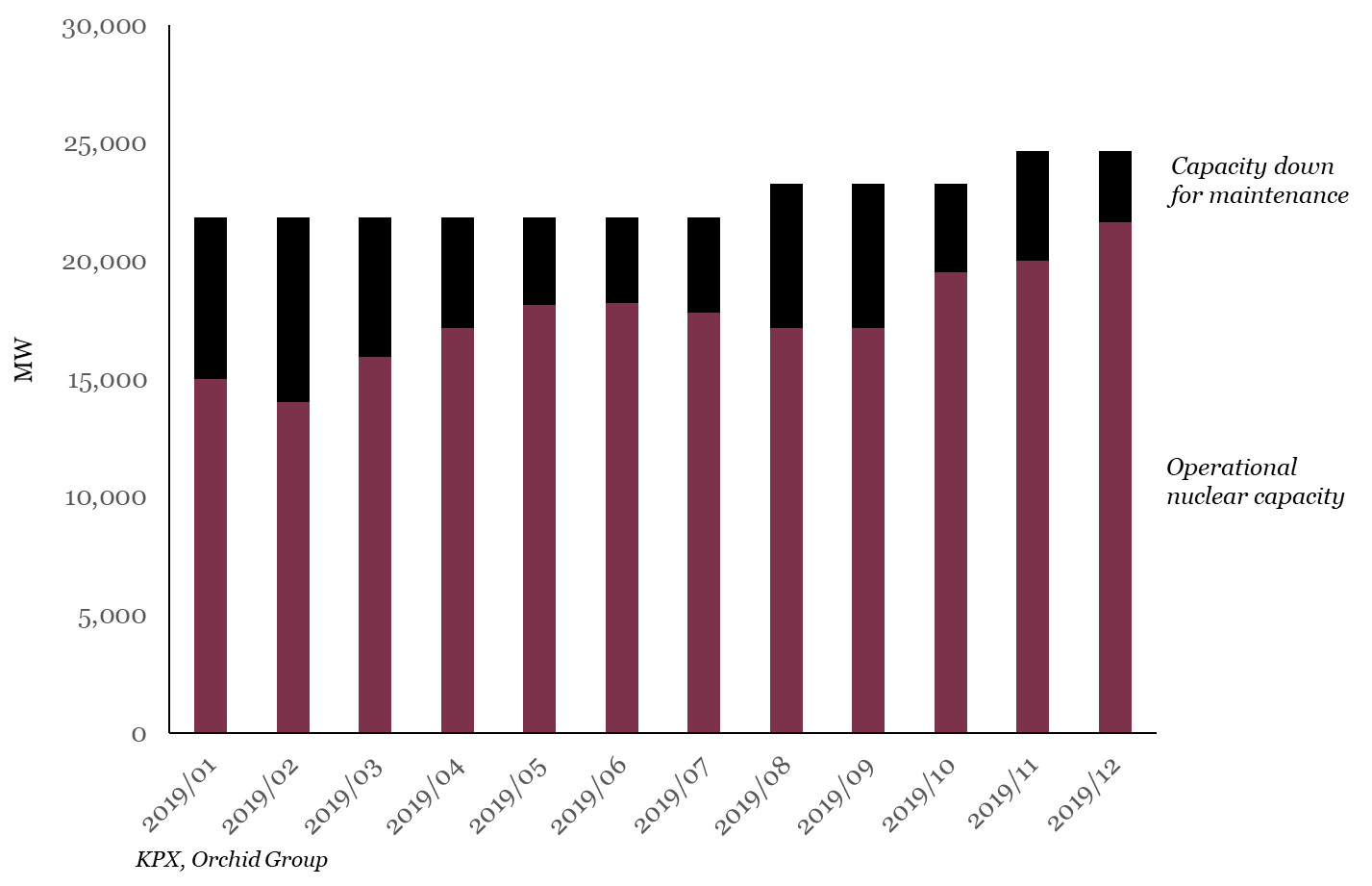

Unfortunately for gas-fired generators, the steep drop in nuclear generation seen in 2018 is not likely to repeat itself this year. The dip was a result of safety inspections and maintenance work under new regulations that saw nuclear operating capacity drop to less 60% in the first four months of 2018 with numerous reactors offline.

In the second half of the year, a number of reactors were back up and running, however not enough to push fleetwide nuclear capacity factors above 80%. With coal maxed out to the extent that the current government will allow, LNG was called upon to make up the deficit.

Nuclear maintenance in 2018

The average capacity factor for gas-fired power plants rose above 40% for the first time in several years. Unfortunately, that remains well below capacity factors of 70% or more that triggered the wave of IPP investment over the past ten years, but it provided an one-year respite from near bankruptcy status for a number of power plants.

Barring an unforeseen development, however, 2019 will see a return to difficult times for gas-fired power plants – apart from those importing their own LNG at favorable terms relative to KOGAS.

Under their operating plan for 2019, KHNP is expected to run its reactors close to flat out. With safety inspections and maintenance largely behind them, most of the reactors in the fleet will be available throughout 2019. There were some issues found during inspections on the Hanbit #1-4 reactors that has resulted in extended downtime, however Hanbit #1-3 should be back online by mid-year and Hanbit 4 before the end of the year.

In addition, a new 1400 MW reactor – Shinkori #4 – received permission from South Korea’s Nuclear Safety and Security Commission to begin operations and is expected to be fully commissioned as early as August of this year. A second 1400 MW nuclear reactor – Shinhanul #1 – is right behind and could be fully commissioned by November 2019.

Nuclear maintenance plan 2019

Taking downtime and new reactors into account, nuclear power generation should reach at least 160,000 GWh in 2019. As a result, gas-fired generation will decline to around 115,000 GWh, roughly the same level as in 2017.

City gas consumption is already lower year-to-date than the same period a year ago due to milder winter weather. If city gas comes in lower than 2018, Korean LNG demand could fall by up to 4 million tons compared to 2018.

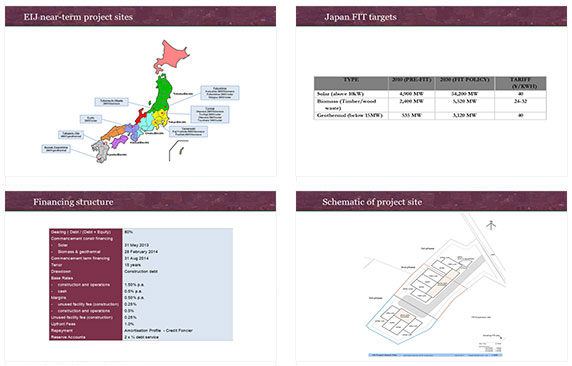

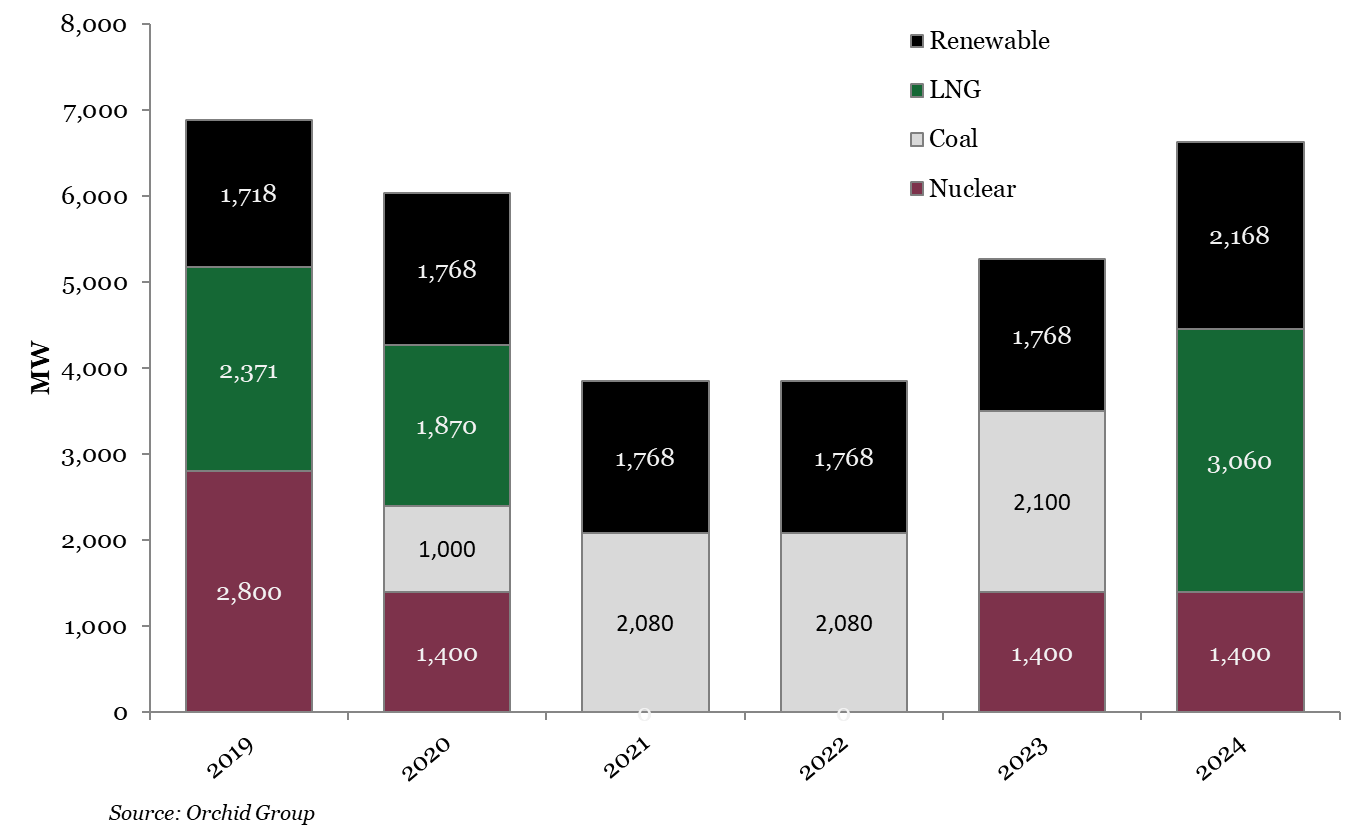

Thereafter, the situation does not materially improve. The Shin Hanul #2 nuclear reactor will come online next year in addition 2020 will see the start of the final wave of coal-fired start-ups. Shin Kori #5 and #6 should start-up in 2023 and 2024 after delays are taken into account. With coal and nuclear pushing gas-fired power further up the merit order, it unlikely that gas-fired generation will reach 2018 levels of production again until 2026.

A cumulative 5 GW of nuclear capacity is currently scheduled for decommissioning between 2023 through 2026. As those reactors come offline – if indeed they do – and electricity demand continues to grow, gas-fired generation’s share of the market will increase.

In the interim, gas-fired generators will continue to struggle to turn a profit, the exception being the direct importers, most notably SK E&S with its Gwangyang power plant and its Paju Energy and Wirye Energy subsidiaries.

New capacity additions, 2019-2024

The caveat to all of this is that the government could take radical steps to curb fine dust pollution, an ongoing issue on the peninsula, that would result in a different outcome from what we anticipate. The government continues to take steps to try and boost LNG consumption, for example, beginning April 1st, 2019 the import tax on coal will be raised from 36 Won/kg to 46 Won/kg while the consumption and import tax on LNG is reduced from 91.4 Won/kg to 23 Won/kg.

However, it is also feasible that at the end of Moon’s five-year term, a new President takes office and undoes policies that are less favorable to nuclear and/or coal just as Moon took steps to undo the policies of his predecessors upon taking office.

For now, however, the opportunity set for LNG producers targeting Korea is likely to be limited to any new direct importers entering the marketplace and the 2024 expiration of KOGAS’ large contracts with Qatar and Oman.